Being patient paid off. I now have Tomb Raider for free.

I remember a time when every trip to the video games store / section was an expensive exercise in decision-making. Do I pick up this Amiga title for $60 today (which is what I remember paying for Ghostbusters II in 1990 or so) or risk never seeing it again? The price of video games was balanced by their scarcity – the physical versions might sell out and there was no guarantee that the stores would be receiving any more of any particular title.

Incidentally, Ghostbusters II on the Amiga was terrible:

But game scarcity is thing of the past – it’s rare for a title to truly disappear, or be out of print. Used game sales and digital distribution means that most modern titles will be around for a very long time. Without scarcity, there’s little chance of games being sold at premium prices for long; in fact, where scarcity increasingly comes into play is during game sales, when it is the discounted price that is only available for a limited time. Gamers have also been trained to wait for the deep discounting of gaming sales, which only serves to push prices down further.

Which is why publishers push the launch period so hard – because if a game doesn’t sell large numbers at launch, it is quickly lost in the gaming market and sales promotions are usually the only lever left to drive purchaser behaviour. Long tail revenue is only usually worthwhile if you sold a huge number of units up front, at least in the AAA space.

On the whole, video games are approaching commodity market status. Perhaps they aren’t commodities in the truest economic sense of the term, but they certainly aren’t a creative product that hold their monetary value for long and are fairly interchangeable in broad terms.

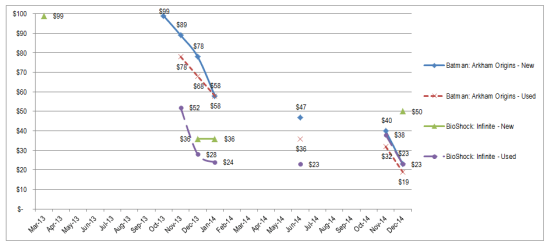

As a point of interest, I tracked the sale price of Batman: Arkham Origins and BioShock: Infinite at EB Stores near me. The following is in Australian dollars:

It’s not a perfect chart and lacks a lot data points, but my intent here is to show that AAA game prices drop very, very quickly… at least at EB Games, who are a pretty big sales channel. (Image sourced from: I created it. Click on the image for a larger view)

These AAA games received solid review scores, but within roughly six months they sold for around 50% of their launch price. (UPDATE 12 July 2015: Because I meant to say this earlier: BioShock Infinite does see an increase in the price of a new copy in December 2014, but that’s because the new version includes the DLC season pass.)

And that’s even if you pay for it, given that video games are often given away free in promotions like they are toys in the bottom of cereal boxes. Both BioShock: Infinite and Tomb Raider were offered for free in March 2015 to Xbox Live Gold account holders. I already (regrettably) paid full price for BioShock: Infinite, but Tomb Raider was a title I didn’t have but had planned to get.

However, since Xbox Live gives me two or so free games each month, plus my existing stockpile of titles that were themselves often bought at a discount, I’d held off buying Tomb Raider just in case.

Through patience, victory. At least for me, the video game consumer.

But I can’t help but wonder for how long such a pricing model can keep supporting gaming. A race towards the bottom of the pricing barrel just makes it harder for studios to make enough money to survive, especially when a studio can spend five years working on a title that receives strong reviews but is still in the digital discount bin the month after next.

With basically infinite supply of games (or any digital content) price should go down towards 0, as per basic economy of supply and demand. Which is why piracy is common.

Scarcity is necessary to even have a price, which is why copyrights will eventually fail, if not already considering everything is in Teh Internets for free. Pay what you want is the only sustainable model in the long run imo. Today it functions de facto (via Kickstarter), while traditionally if I think game is worth 10$ and price tag is 20$ I won’t buy it until sale (if I remember I wanted it).

Also if my monthly game budget is 100$ I can buy 2 50$ titles or 10 10$ titles or…. 100 1$ titles.

Then there is economy of scale. Producer can sell 1000 pcs for 50$, but 100000 for 1$, because many more people can afford it, and risk/reward ratio becomes negligible at one point, so people start buying it even if they won’t play. Many does it already because of impulse sales. Speaking of which, I think platforms like Steam basically probe the market for acceptable prices through sales.

Then game production is sunken cost, and once it’s done you can have infinite copies.

I think we’re in intermediate period, with online sales killing physical distributors eventually, maybe except for collector’s editions.

Collector’s Editions are an interesting thing because they really overcharge for bunch of cheap(ish) but limited edition items. The game is still usually the same, but it comes with shinys that cost the gamer another $30+.

And yeah, it’s entirely back to charging for that scarcity.

And even if they give you some ingame exclusive stuff, they will release it later as DLC for everyone, so people won’t even have bragging rights.

Btw I remember buying cRPG back in 90s, I got 3 diskettes, detailed map of area, great manual, all printed in colour. And it was standard release. It wasn’t cheap, but I felt money well spent.